EMTALA: The ER PA's Guide

In this post, we begin to tackle some of the complex legal framework that ensures our job is never, ever boring—or at least, never free from the threat of huge fines: the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA).

For those of you who just started in EM, EMTALA is essentially the Hippocratic Oath for the ER, written by lawyers, backed by the federal government, and enforced with hefty financial penalties. Fun!

As an experienced PA, I’m here to give you the unvarnished, slightly jaded truth about this law, how it came to be, and why it affects every single patient encounter, from a stubbed toe to a STEMI.

In short, EMTALA outlines critical federal regulations that govern emergency medical practice, enacted to ensure patient access to care (i.e. EVERYONE who comes to the ER). EMTALA imposes rigorous standards regarding assessment and stabilization that you MUST understand as a practicing PA. Compliance with this law is absolutely essential, as violations carry significant financial penalties enforced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Historical Significance (The Bad Old Days)

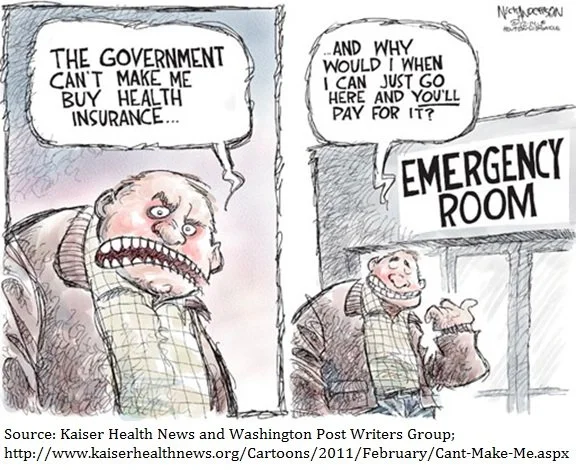

Before 1986, the emergency department could act like a fancy restaurant. If a patient showed up without a suit jacket, say uninsured, or simply too complicated, hospitals could—and often did—shuttle them off to the nearest public facility. This elegant practice was known as patient dumping.

Ah, simpler times, when corporate finance dictated clinical care.

The problem, however, was that real people in real emergencies were dying. So, Congress—bless their bureaucratic hearts—decided to intervene. They passed EMTALA, which basically told hospitals: "Look, if a person shows up, regardless of their ability to pay, you are required to assess and stabilize them."

EMTALA mandates that all Medicare-participating hospitals with emergency departments must provide a standardized level of care to any individual requesting evaluation for an emergency medical condition, regardless of financial capacity. The statute thus elevates the ethical obligation of emergency medicine to a matter of federal law, requiring meticulous adherence to documentation standards to mitigate institutional and individual liability.

This is all under the threat of stiff financial penalties if a hospital/ER doesn’t fulfill its EMTALA mandates. Interestingly, this mandate that “covers” anyone who shows up to the ER isn’t backed by any federal financial aid for those hospitals who do care for those patients who don’t pay (but more on that later).

“If any individual comes to the emergency department, and a request is made on the individual’s behalf for examination and treatment, the hospital must provide an appropriate medical screening exam within the capability of the hospital’s emergency department, including ancillary services routinely available to the emergency department, to determine whether or not an emergency medical condition exists.”

The Legal Requirements

(The Three Commandments of the ER)

EMTALA boils down to three core, non-negotiable requirements. Memorize them. Tattoo them on your documentation hand, if you have to.

Everyone who presents for evaluation must receive a Medical Screening Exam (MSE) by a Qualified Medical Person (QMP).

Every patient determined to have an Emergency Medical Condition (EMC) must be treated and stabilized before transfer or discharge.

An unstable patient may not be transferred unless the transfer is medically necessary and affords the patient greater benefit than remaining at the originating facility.

Pretty basic stuff that unfortunately came out of some pretty horrible cases of people being turned away without treatment or being sent to another hospital while unstable and dying. The idea here is we see and treat everyone, every time. Every patient needs to be evaluated and stabilized before going home or out to another hospital. Even if a hospital doesn't have the medical or surgical specialty care needed for a particular type of patient, they cannot be refused and must be treated and stabilized before transfer to a hospital that has the appropriate specialties.

I. The Medical Screening Exam (MSE)

The Rule: Any individual who comes to the ER (or hospital campus) and requests examination or treatment for a medical condition must receive an MSE.

The PA Reality: This is where we can shine as clinicians. You must execute an MSE that is consistent with the established hospital policy for all similar presenting symptoms. Whether the patient comes for a paper cut or a liver lac, the screening must be sufficient to determine, with reasonable clinical certainty, whether an Emergency Medical Condition (EMC) exists. This determination requires a thorough, documented history and physical examination, thereby serving as the primary defense against allegations of improper assessment. Failure to complete or adequately document this process constitutes a violation of the statute, so document, document, document.

Translation: You can't just glance at the patient and say, "Nope, not an emergency." You need to rule out an EMC with a proper, documented history and physical. Yes, even for the patient demanding a work release for a cold that started 20 minutes ago. Your documentation of that history and physical is your shield.

Caveat: This MSE must be performed by a Qualified Medical Person (QMP) - which every PA should be qualified to do, but ensure that your the hospital's bylaws explicitly designate PAs to perform this function!

II. Stabilization

The Rule: If you determine an EMC exists, you must provide treatment to stabilize the patient.

The PA Reality: This is the commitment clause. You own that patient until they are stable enough to be transferred or discharged. This is why we don't discharge the guy with chest pain that resolved until the troponins are clear and the EKG is benign. It's also why patients in active labor are untouchable—you stabilize (deliver) them, or transfer them appropriately. You, as a PA are responsible for ensuring that all appropriate diagnostic, therapeutic, and consultation services are initiated and completed until the patient meets the criteria for stabilization. This means an unequivocal commitment to the patient’s care until safe disposition is secured, which, by the way, should be documented (including all your decision-making making such as consults and clinical decision aids)!

Caveat: This is why transfer paperwork always asks if the patient is "stable." However, unstable patients may be transferred if the benefits outweigh the risks (see below)

III. Appropriate Transfer

The Rule: You cannot transfer an unstable patient unless the transfer benefits the patient.

The PA Reality: The transfer is a bureaucratic ballet. If a patient requires a higher level of care (like a burn unit or specialized neurosurgery), you have to jump through these hoops:

The receiving facility must possess the necessary capabilities and formally accept the patient.

The transfer must be justified by medical necessity, as the transferring hospital lacks the resources to manage the patient's condition.

Qualified personnel and specialized equipment must be utilized throughout the transfer process.

Every transfer requires detailed documentation and communication that the transfer is appropriate and that all attempts at stabilization were made. If a patient refuses transfer, that refusal must be documented clearly. Any instance of a patient refusing necessary treatment or transfer must be documented in exhaustive detail, confirming that the risks and benefits were fully explained and stabilization was offered until discharge criteria could be met.

EMTALA and the Everyday ER PA Practice

For us PAs, who are often the first, second, and third line of defense, EMTALA is mostly about documentation, documentation, documentation.

The Elopement: The patient signs in, waits three hours, and leaves (Elopes). If they didn't receive an MSE, it's an EMTALA violation. <comment-tag id="5">Your saving grace? You must document that an MSE was offered and that the patient walked out against medical advice (AMA), hopefully with a signed piece of paper, but at least documented by the nurse and yourself.</comment-tag id="5" text="Your saving grace? You must document that an MSE was offered and that the patient walked out against medical advice (AMA), hopefully with a signed piece of paper, but at least documented by the nurse and yourself. Ensure your note includes the time the offer was made, the location (e.g., waiting room), and the specific witnesses." type="suggestion">

The Parking Lot Problem: Did the patient only make it to the parking lot and then have their baby? Guess who has EMTALA liability? Your hospital. EMTALA applies to the entire campus. If you are called to the parking lot or the front lawn, the clock is ticking.

The Refusal to Consent: The patient is clearly unstable (EMC present) but refuses care. You must document, in excruciating detail, the risks, benefits, and alternatives discussed, and the fact that you offered stabilization until they could be discharged safely. <comment-tag id="6">Your notes must read like a deposition transcript.</comment-tag id="6" text="Your notes must read like a deposition transcript. Specifically include the patient's capacity to refuse care and the identity of any family or police present for the discussion." type="suggestion">

Final Takeaway

EMTALA is a necessary evil that protects vulnerable patients and, frankly, makes our job more ethically sound. But, for us in the ER, it’s a constant, nagging reminder that every chart is auditable and every decision has legal weight.

So, clock in, get your Medical Screening Exams done right, stabilize those who need it, document your soul out, and always remember: the best defense against CMS is a fully completed, perfectly legible, and legally unassailable medical record.

Now, go forth and chart responsibly. And try not to think about the lawyers.

Under EMTALA laws, what must an Emergency Department do???

The Law...

Of course, with all laws, much time and consternation must be spent on defining the above terms, so here you go.

The phrase "comes to the emergency department" was broadened (I mean really broadened) to include 250 yards around the main hospital building. This includes parking lots and sidewalks where, unfortunately, some patients are dropped off by their "friends." In fact, it was a case like this where a young man who had been shot was dropped near the ambulance bay of a hospital but not taken in because it was assumed that EMS would take the patient to a trauma center. Talk about callused. That hospital got in trouble and now we have the 250 yard rule of areas surrounding the hospital (but obviously not including other businesses/offices).

In other words...

Even if someone is only brought to the sidewalk adjacent to your ER, you are still responsible to provide a medical screening exam. Got it? EMTALA mandates screening anyone within 25o yards of your hospital who is presenting, or trying to present for an exam.